THE GALLERY - DARRAH LESTIDEAU

Capturing beauty

At the very beginning of her artistic life, having just finished high school, Darrah Lestideau already carries herself with the air of someone who has spent years thinking carefully about what art is supposed to do and what it demands of the person making it. Her work spans across intricate portraits, expressive oil studies, and sculptural reliefs, all suggesting an artist deeply attuned to the human figure, and to the quiet, private worlds that those figures carry with them.

Though her style appears mature, she insists she is still “finding her feet.” Her process, she says, begins not with a concept, but with other people’s art. She likes to work “armed with artistic influences,” surrounding herself with books and images. “I take the elements I like most and fit them together into something new,” she explains. “I think I do this because I'm scared of making it up, I can't pluck things out of thin air like some of my other creative friends. If I'm faced with a blank page and nothing around me, I feel completely lost.”

It’s an unexpectedly candid admission, especially from someone whose work displays such command. But it reveals what runs quietly beneath everything she does: a respect for artistic lineage, a desire to understand the craft before reinventing it, and a belief in learning through observation rather than uncontrolled spontaneity.

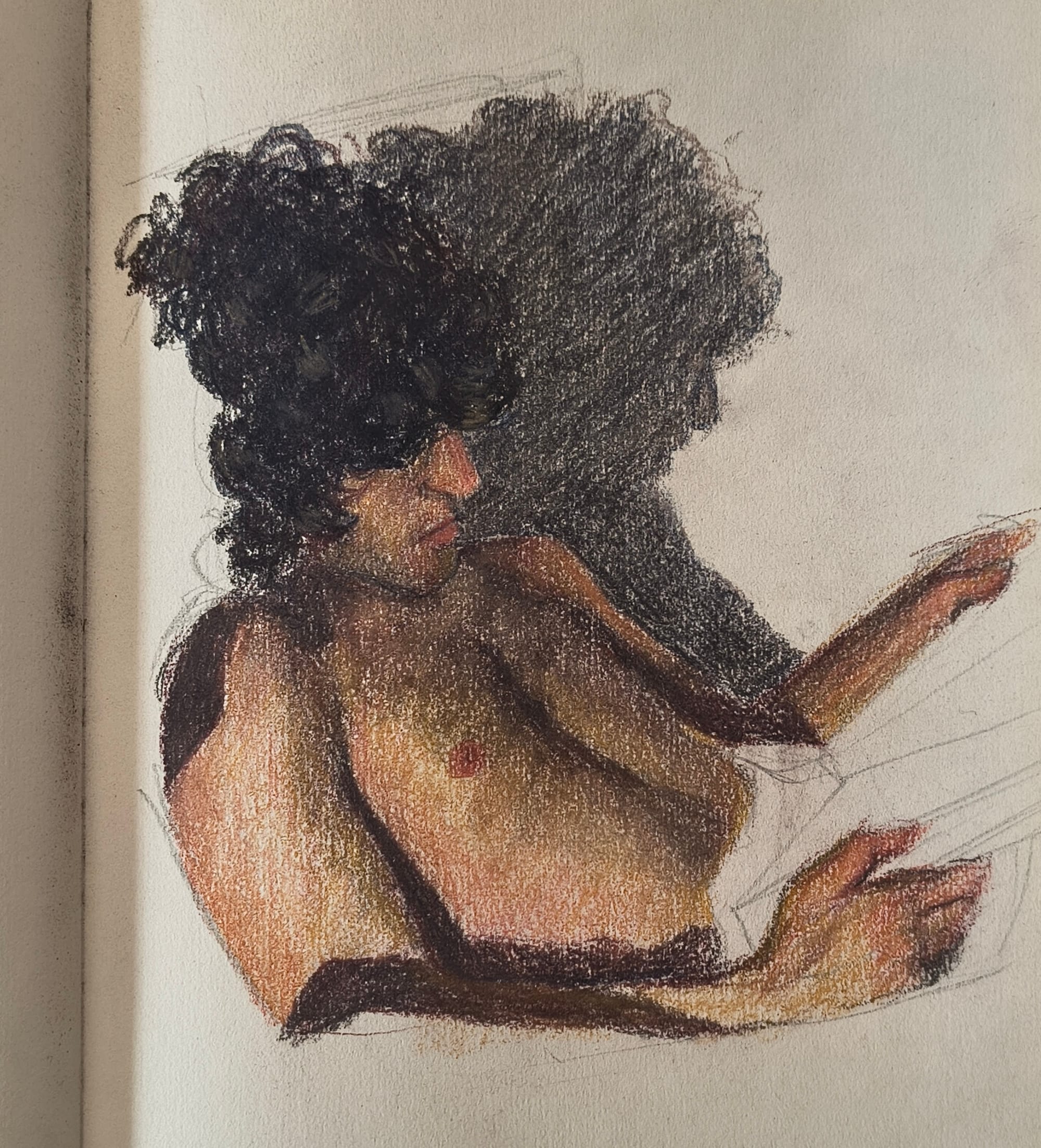

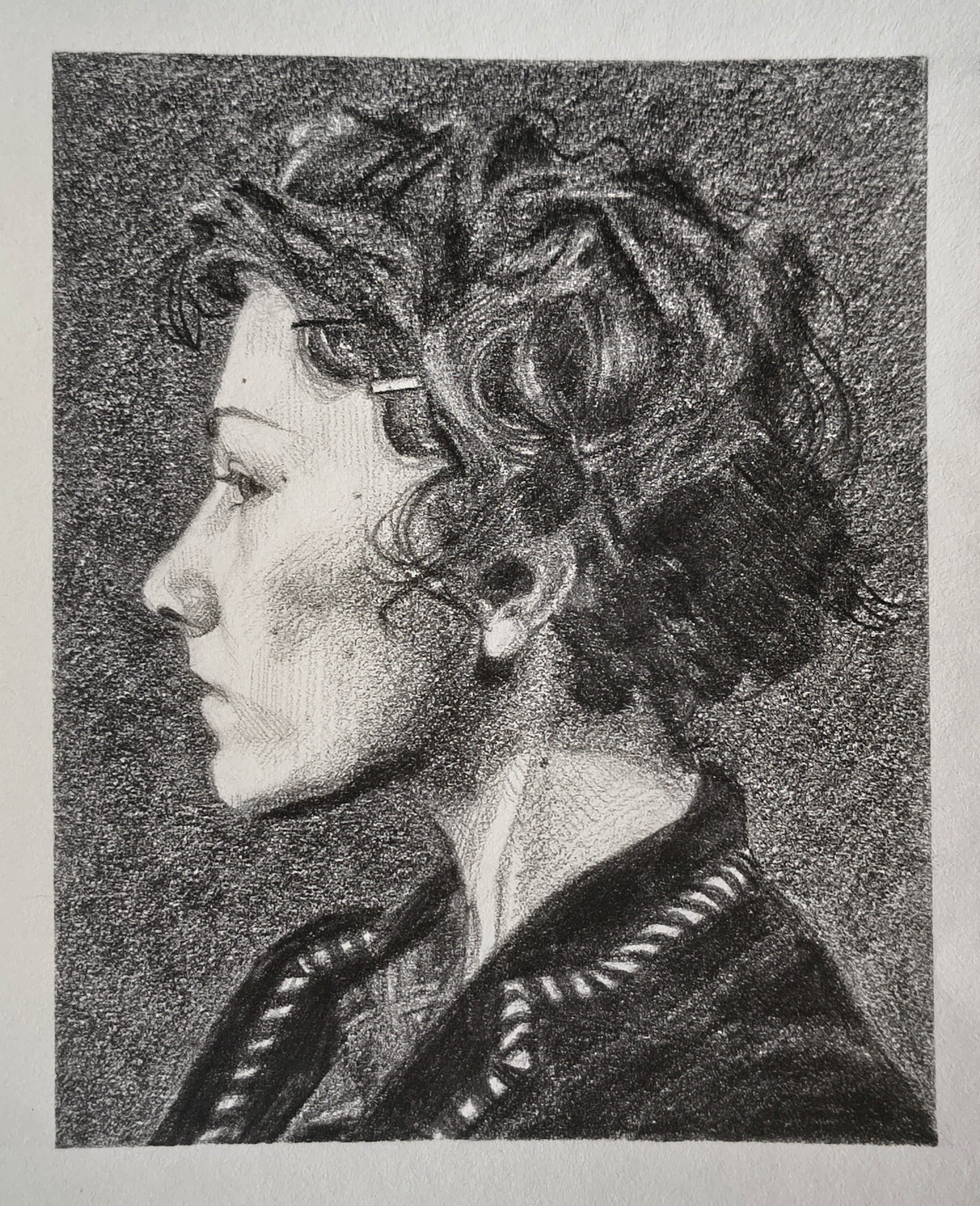

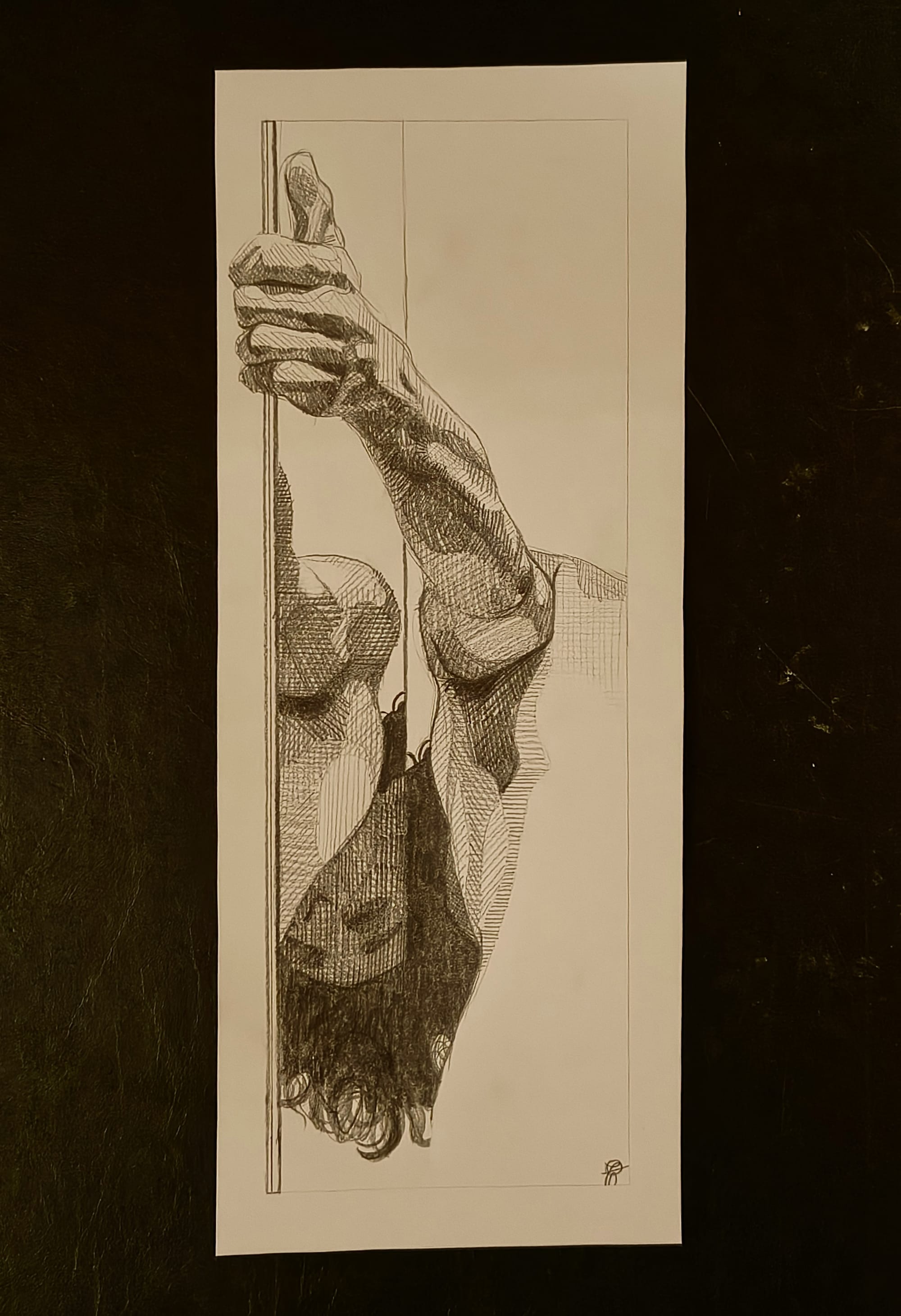

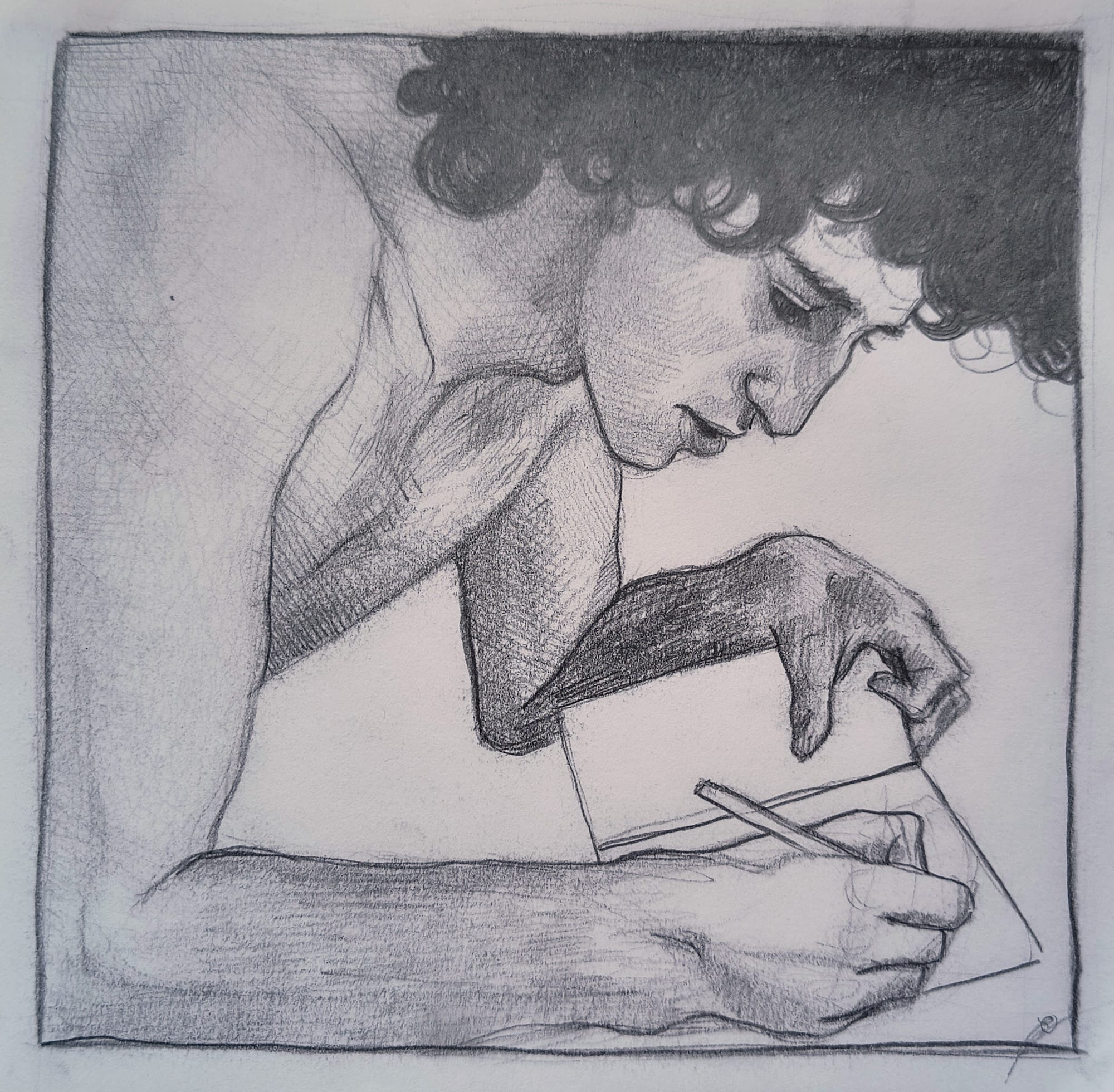

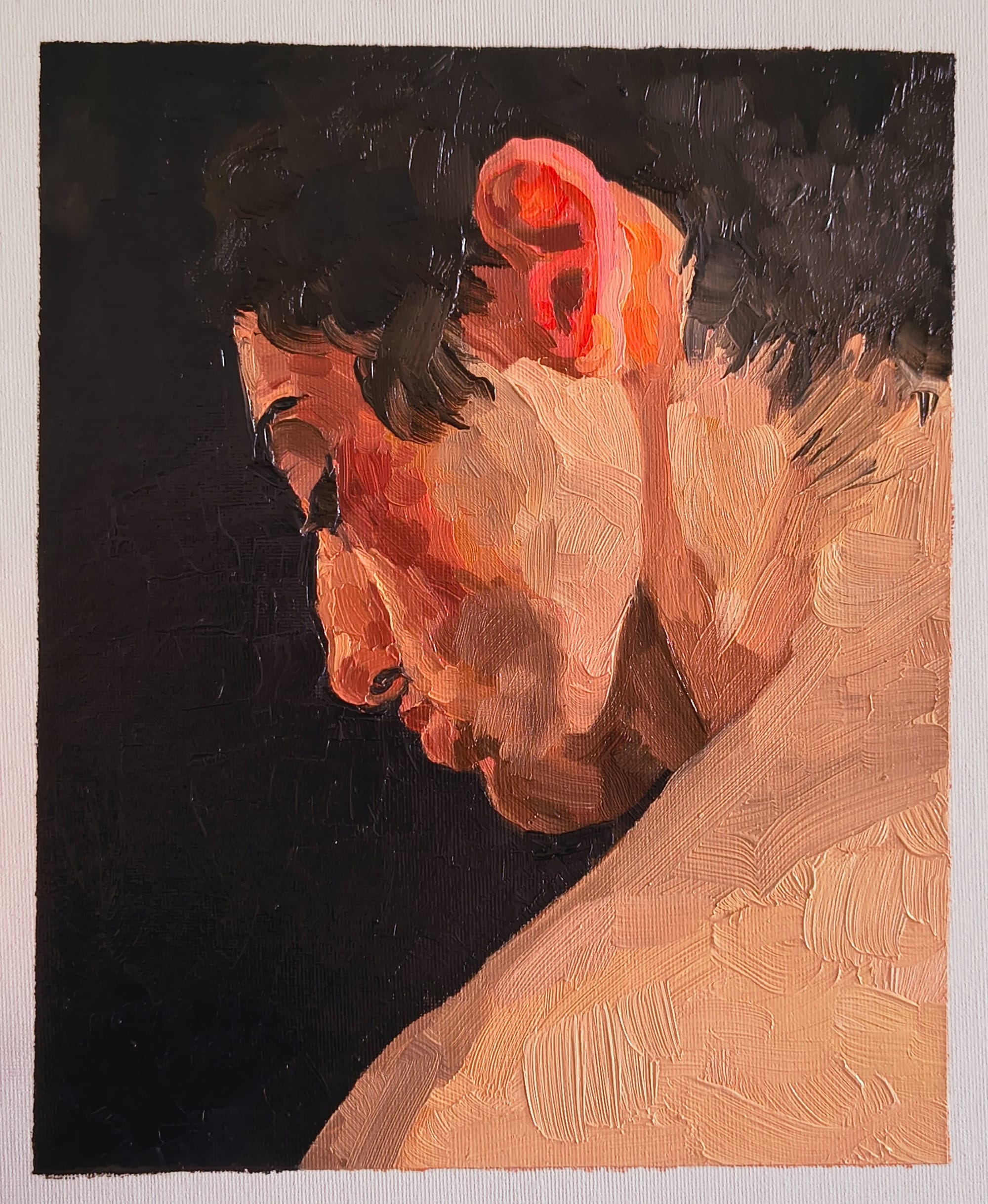

From left to right: Reader and shadow; Side Eye; Luca

Portraiture as a way of seeing

Much of Lestideau’s recent work focuses on the figure; portraits or self-portraits, executed with a technical precision that belies her age. Yet she admits she has grown restless with realism for realism’s sake. “Right now, I do a lot of realism and figurative work,” she says. “I don't like this anymore.” Before finishing high school, she says, she'd never had the expansive time required to dig beneath technique to find a conceptual foothold. Her drawings, by her own assessment, “lacked intentional thematic complexity.”

Yet a moment of accidental self-analysis came when she pinned a year’s worth of portraits of her boyfriend to a wall. Every single one was in profile, or captured over the shoulder. “He's an evasive man; I never really feel like I have him,” she reflects. “Somehow, that’s worked its way into every drawing I've ever done of him.”

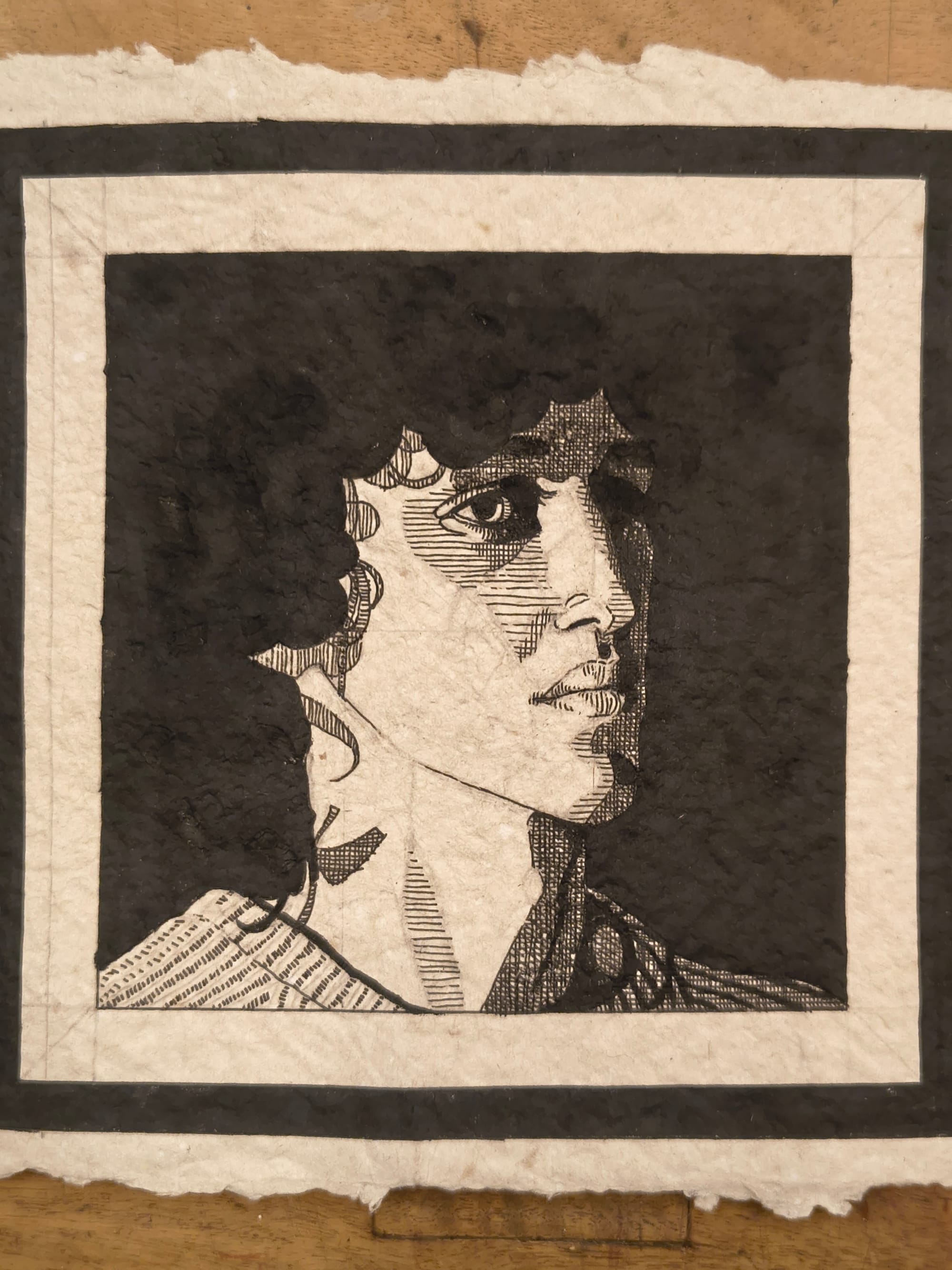

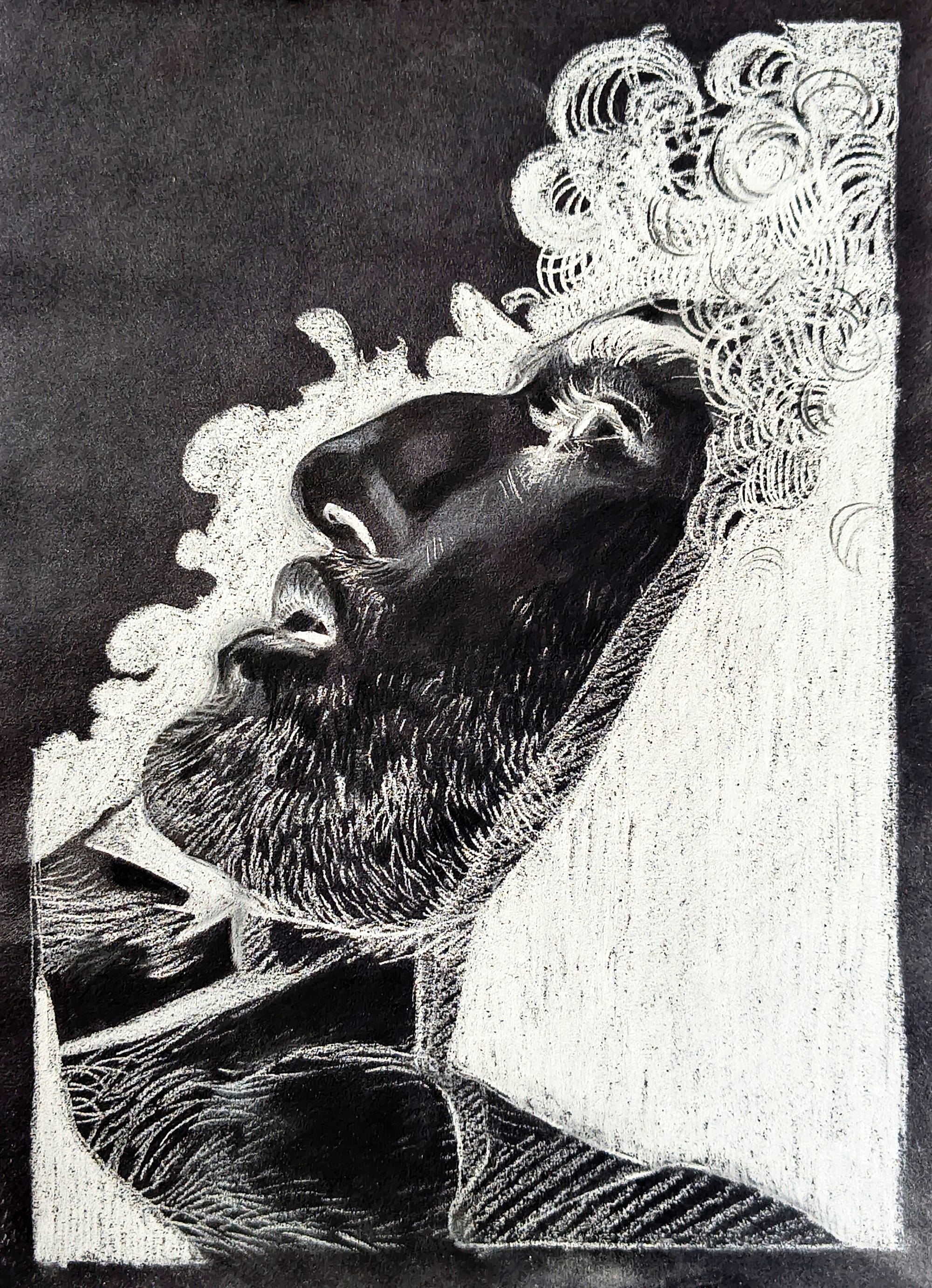

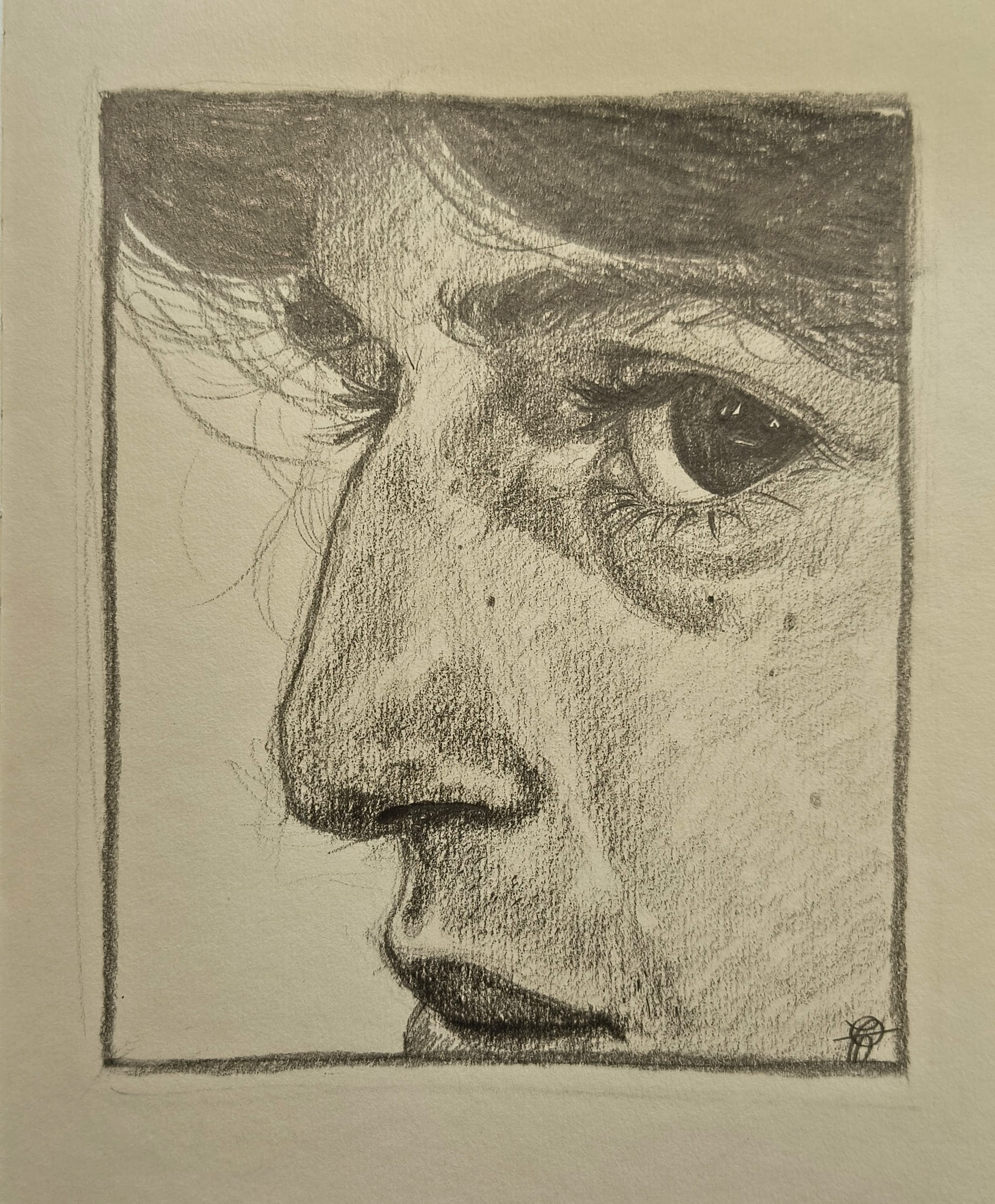

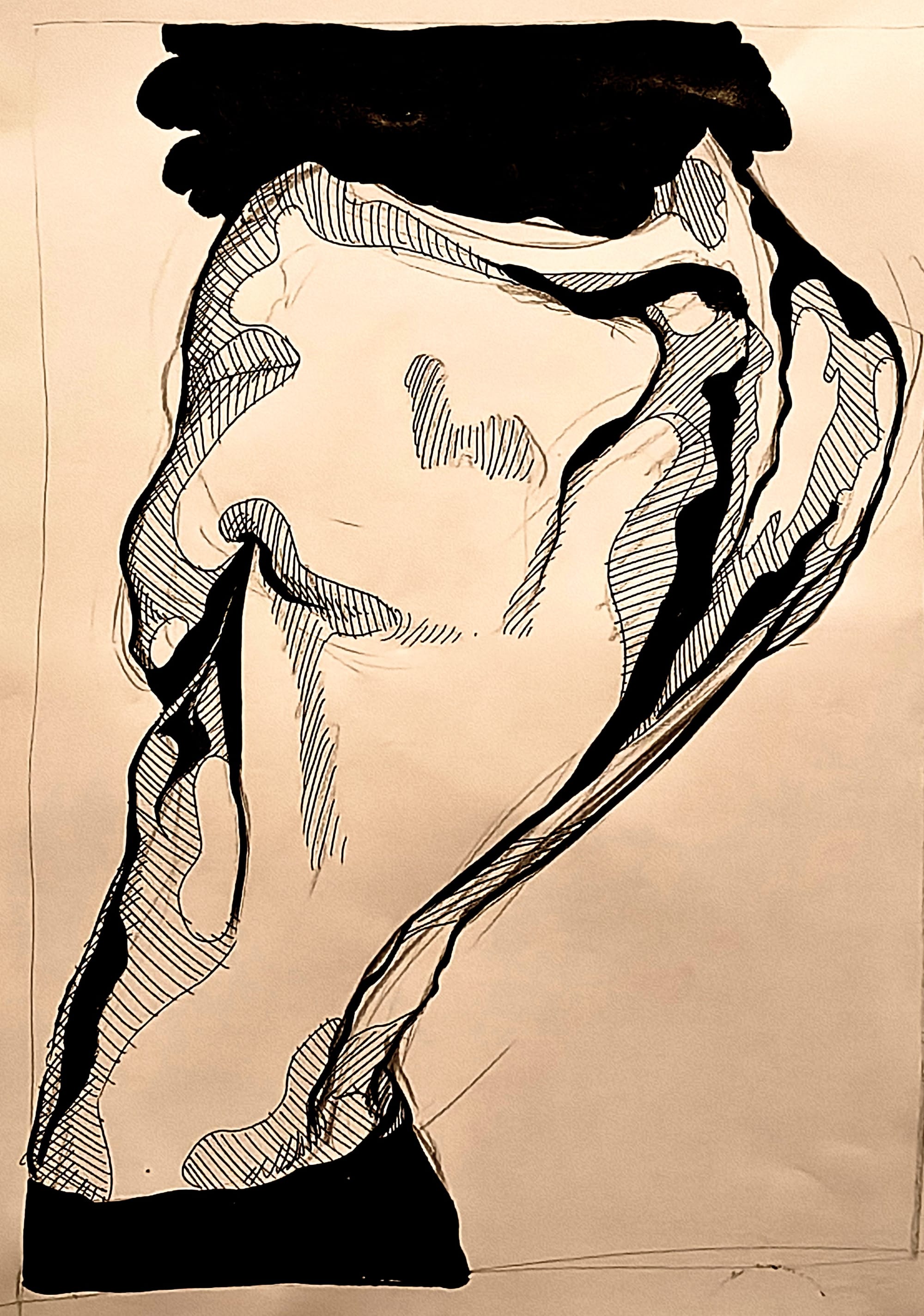

The observation is not only revealing, it’s visible in the works themselves. The images, these sweeping graphite portraits, textured pastel pencil studies, stark black-and-white ink drawings, they capture men in moments of inwardness rather than dominion. Shoulders turn away, expressions recede, bodies fold into their private thoughts.

This isn’t accidental. It’s emotional, deeply personal, almost political. “Throughout history,” she says, “men have been the artist, the observer, and women, the muse, the observed.” She considers this “a shame for both sexes,” because it deprives women of agency, and men of being seen tenderly. “The long and the short of it is that I think men are beautiful and I want to paint them as beautiful; not chiselled or commanding...beautiful.”

The works reflect that intention clearly. Its figures are attentive, emotional, reverent. They are also grounded in a kind of empathetic realism, an insistence on representing men as privately emotional rather than stoic.

Left to right: Luca, Inverted; Reflection in a Glass Door; Est-ce Que Je Peux Avoir un Bisou ?

A city that shapes the work

Geelong also plays a formative role in Lestideau’s developing style, not only as a community but as a landscape. She recently received a residency at Liminal Gallery, “the best thing that could possibly have happened to me after exams,” she tells us. The residency granted her her first real studio: “a quaint little spot above the gallery, overlooking Ryrie Street and the Geelong Arts Centre.” For the first time, she isn’t worrying about turpentine fumes in the family home or spilling paints on the floor.

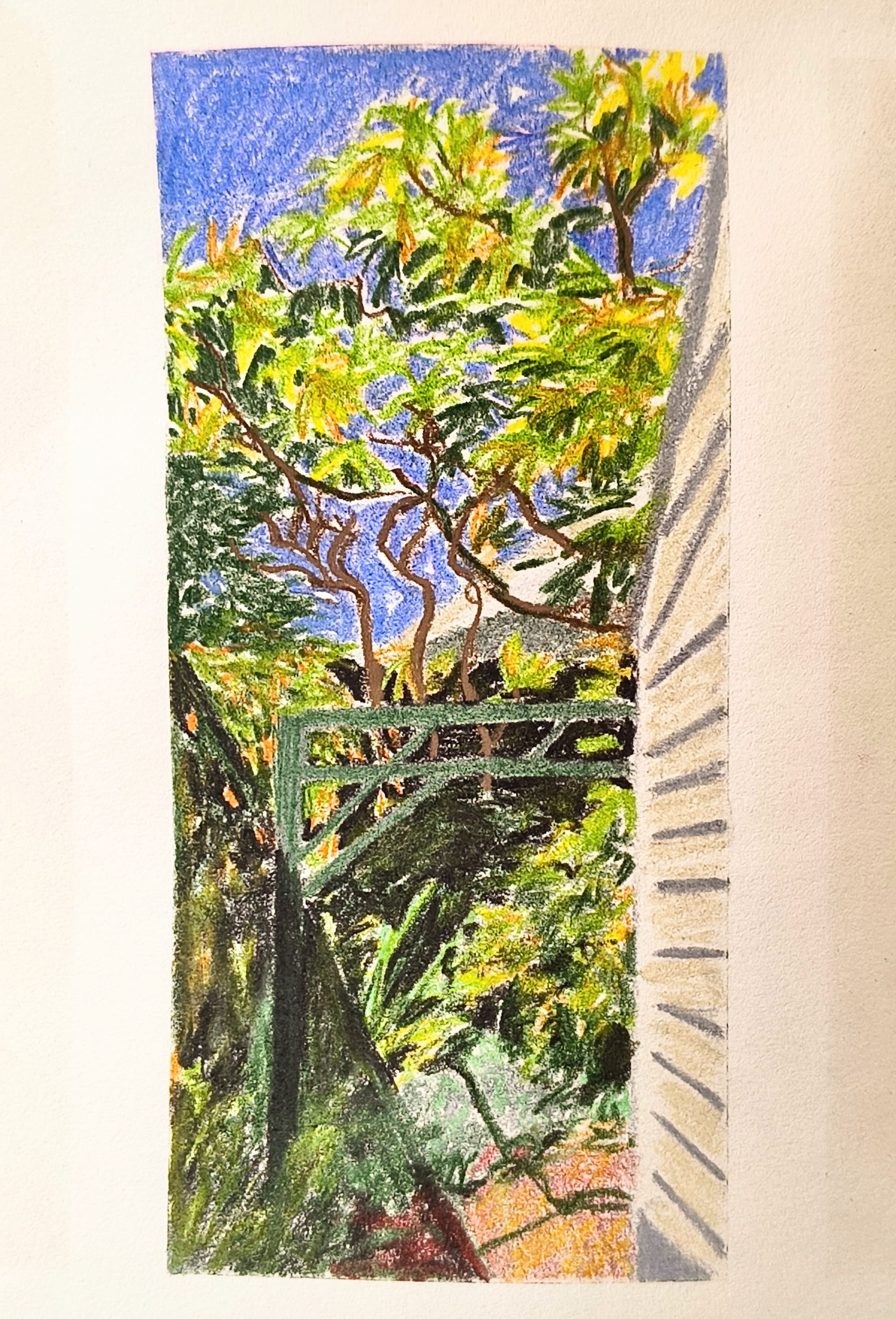

Liminal has also given her the opportunity to exhibit in their upcoming 9 x 5 Impressionist exhibition. These small invitations, she says, are invaluable: “perfect for getting the experience and exposure I need to get a foothold in the Geelong art community.”

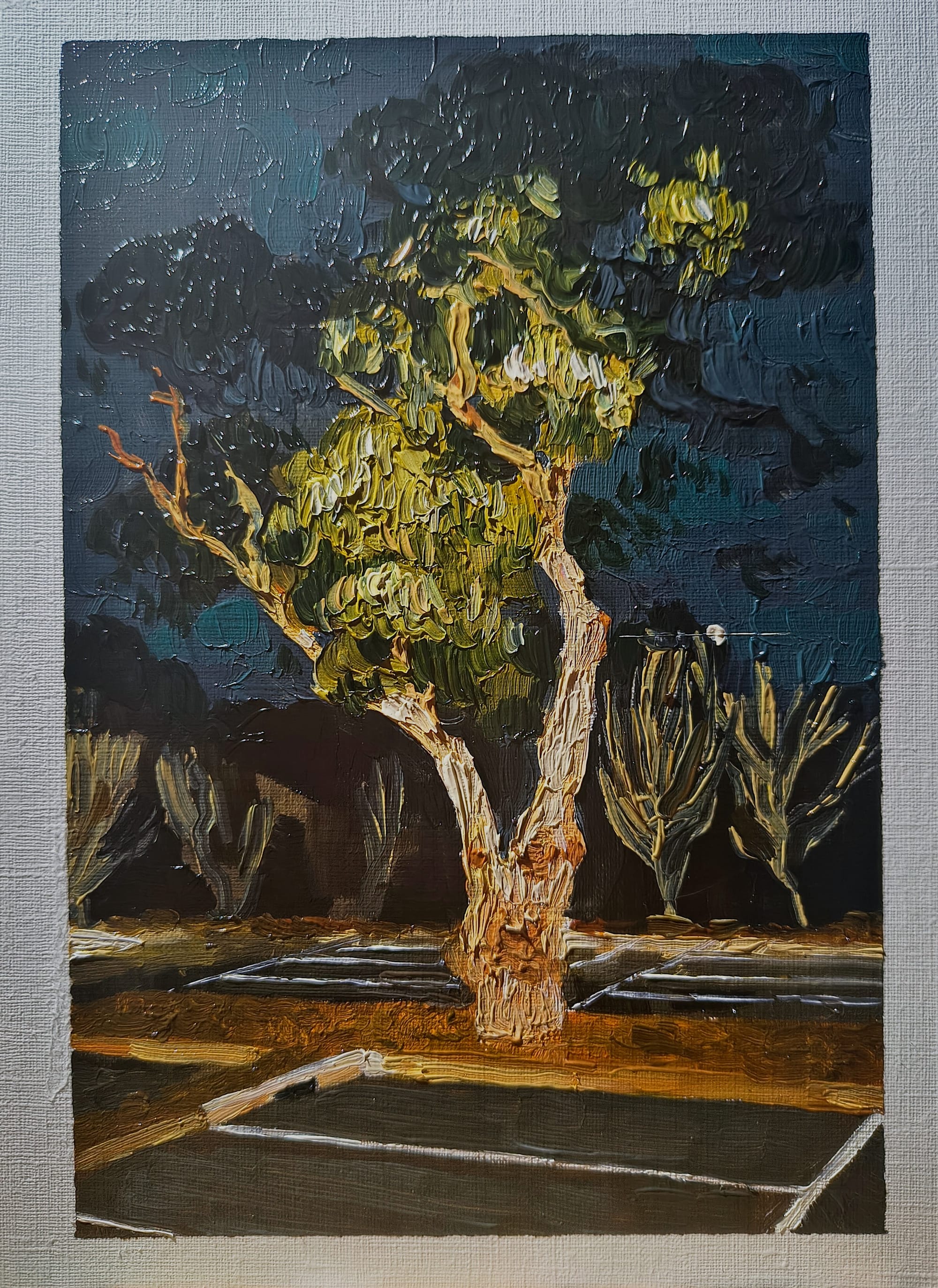

But the city has shaped her more intimately too. When she and her boyfriend started dating, they would walk through the suburbs before sunrise in quiet, bluish streets, under yellow pools of streetlights among the strangeness of houses before day has begun. She believes “Geelong is at her most beautiful then,” and it shows. Her oil studies of nocturnal trees, their branches glowing against deep grey skies tinged with phthalo green, are mesmerising. “Slightly eerie,” she says. But unease is part of their charm. These paintings make suburban trees appear mythic, as if illuminated by stage lights.

Left to right: Woolies Run; 5amer

Three Ages and a Future: a work transformed by accident

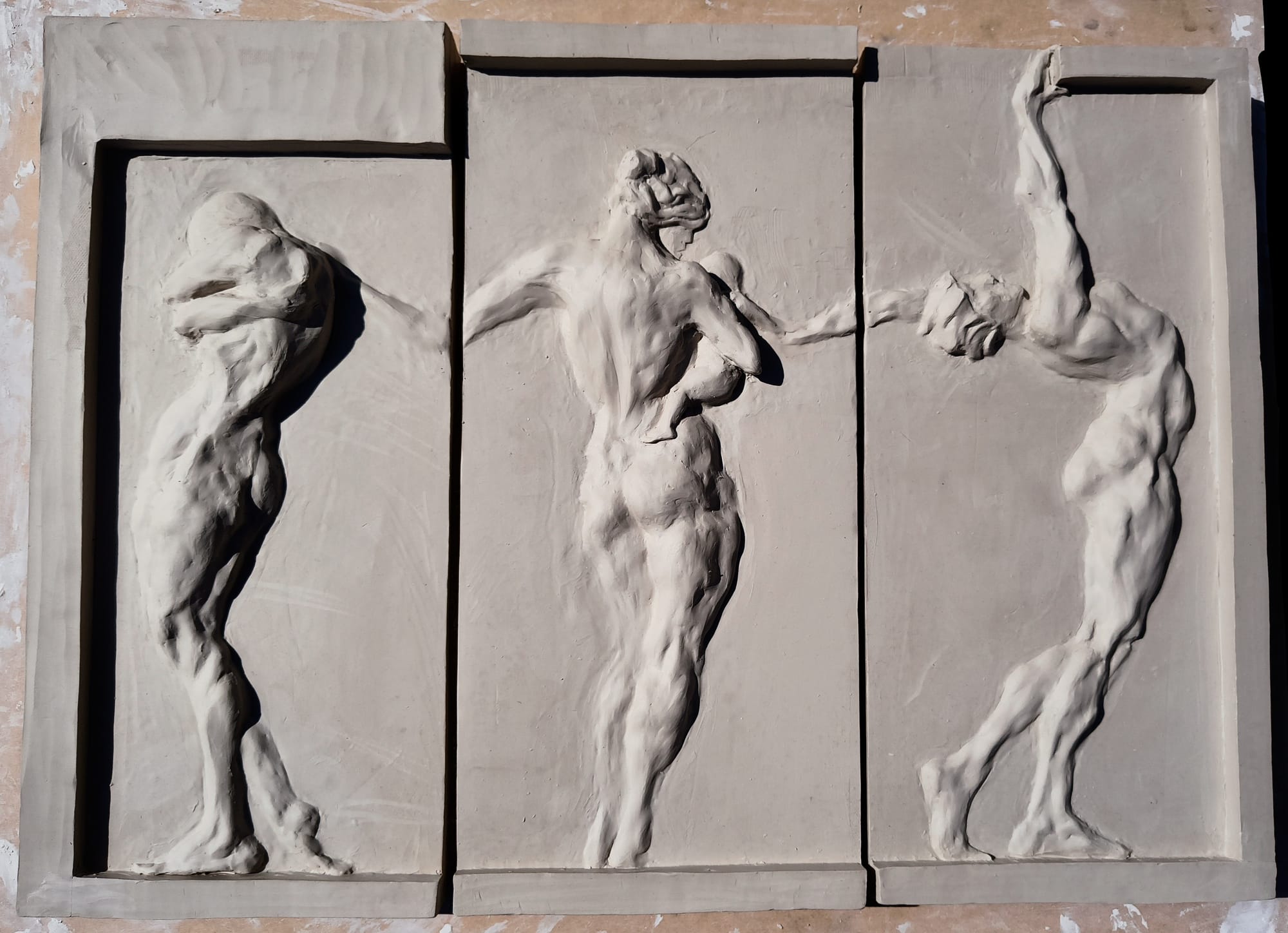

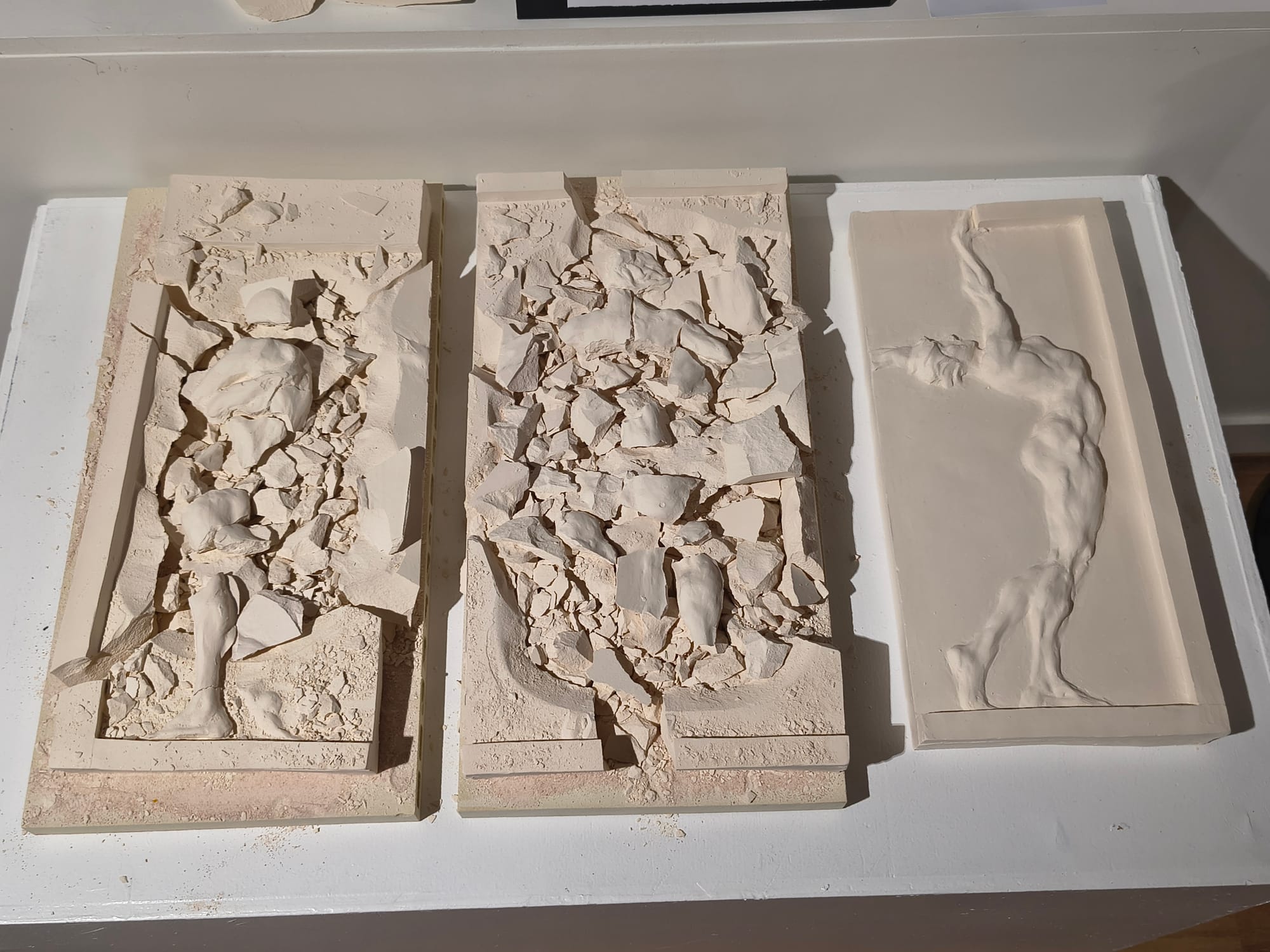

The most defining project in Lestideau’s young career is Three Ages and a Future, a relief sculpture created for her Year 12 art project. Inspired by Klimt’s Three Ages of Women, the work was originally comprised of three clay panels containing four figures, each representing a different period of her life.

The first depicted “the exaggeratedly tortured form of my past,” a younger self overwhelmed by hormones, loneliness, and the echo-chamber of angsty misery of social media. The next figure was a possible future, a mother cradling a child that was simultaneously her childhood self and her imagined child. The final panel represented her present: a figure bent backward under the strain of Year 12, “but looking up through a gap in the frame,” symbolising her drive toward becoming an artist.

“It’s about how people change so much in one lifetime that they transform into many personas almost unrecognisable to one another,” she says. “It’s about how change is inevitable, and self is of the nature of impermanence.”

Then came the twist, the kind an artist can’t plan for but sometimes needs. On the morning of the exhibition, the kiln was opened, and two of the panels had exploded from within. “I promptly went back to bed, cried myself to sleep, and bitterly resolved not to go,” she admits. The clay was still damp inside and had imploded. Only the present panel survived.

After the initial heartbreak, she recognised something strangely poetic. The destruction echoed a Buddhist teaching she had grown up with: that only the present truly exists. “We can’t rely on the future to make us happy; we only have control over our attitude toward the present,” she says.

Before and after the kiln disaster

She included a Jack Kornfield quote beneath the work:

“We are always in the eternal present… The past is just a memory, the future just a thought.”

The fractured work went on to win the sculptural prize. The tragedy deepened the piece, transforming it into something raw, accidental, and resonant.

Technique first, concept second

Lestideau is clear about what she wants art to do, both for her and for her audience. “I'd like to reintroduce a reverence for technique and figurative skill,” she says. Abstraction, she admits, is often lost on her. Connection comes first through the eye, then the idea. “I want people to see the work and appreciate the way it looks… connect to the colours and atmosphere first, concept second.”

Her drawings exemplify this. Whether they are the graphite portraits, dense with cross-hatching and subtle tonal shifts, the attention to bone structure and light, or her oil paintings, thick with texture in big, confident brushstrokes building luminous skin tones or suburban foliage.

And yet, under all this technique lies something tender. Her influences, Klimt, Schiele, Metzner, Sarazhin, are united not only by their skill but by their sensitivity to human presence. That sensitivity is what her work seems to return to again and again.

What comes next

For Lestideau, everything up to this point has felt like rehearsal. “What I have so far is the result of a spare half-hour or a school-regulated project,” she says. Now, with a studio, a residency, and endless time before her, she is planning her first solo exhibition for late March. “My real body of work is yet to be made,” she says. “I’m looking forward to seeing what I can come up with.”

Given the breadth and maturity of what she has already produced, that statement feels less like humility and more like a promise. Whatever comes next for Darrah Lestideau will almost certainly be shaped by the same force that accompanies everything she does: devotion to beauty, reverence for craft, and an artist’s quiet, persistent desire to understand the people she draws, not as symbols or archetypes, but as whole, beautiful beings in eternal present.

You can see more of Darrah's work and learnings on her instagram.

Fancy sending us some of your artwork? Just email us at geelongcereal@gmail.com.

Have you subscribed? Go on. It helps us and it means we can send our new articles straight to your email. Subscription is free and gets you full access to everything on Geelong Cereal.